Sight Unseen / Brandon A. Evans

The inscription on the inner wall

In a distant land, there is a fictional monastery and over its church is a stone mantle. Inscribed there are three words its monks read every time they gather to prayer:

In a distant land, there is a fictional monastery and over its church is a stone mantle. Inscribed there are three words its monks read every time they gather to prayer:

“All Things Pass.”

It’s a phrase they keep in their hearts and use to stoke the fire of their fervor; a lock-solid rule set against a vain world.

For humanity is, in its progress and regress, human. The fault at the heart of the world is the fault at the heart of each person, and despite all attempts every generation forgets the things it promises it will not.

Original Sin wounds us. It makes to stumble the steady and lends darkness to memory. We repeat, from children to adults, the mistakes of the past because they are our mistakes; the fissure that separates us from God cuts down all the way to the deepest part of our souls.

We are a paradox: beings who long for permanence and immortality in a universe of constant change and death—even our good works betrayed by our mistakes.

We tremble before death, and against all our hopes history staggers toward apocalypse.

But it is precisely there that we find our hope, for the light that shines at history’s end is the light of the One who made Easter out of Good Friday.

The monks of the imaginary abbey live the words they read each day by seeing in them not just a curse, but also a remedy. They live a life of detachment and austerity, dying to the things they want the most and giving their service to God.

Jesus Christ is the very model of this cure. Over and over in the Scriptures, he says it: that we must each take up our cross, give up our possessions, accept the tears that come our way, turn the other cheek. He says it until, in the end and despite his fear, he embraced death willingly.

One day it will be each of us standing before that darkness. It will be us on the hospital bed, unable to move as the priest lays down crosses of oil on our hands.

Our own death will be—to each of us—the death of everyone and everything we know. All our plans, all our loves, all our hopes and dreams and memories, they will all pass in a single instant. We will cede all ownership, even of our own body.

Our lives can be a preparation for such a moment, having placed our trust in Jesus a thousand other times and through a thousand other worries; we can steal from death the terror it wields.

For it is just as our last breath leaves that we will see the deeper truth that lies beyond the words on that monastery’s mantle. We will come to realize the power of Christ’s promise to make all things new, and to give good things to those who relinquish them.

We will see that every word we have spoken, every bond forged, every lesson learned, every glimmer we have ever had in our eye, every love, every friend and family member and home and city and memory did not, after all, pass into nothingness.

They passed into another’s ownership, to the One who breathes new life into them and will hold them for us forever.

C.S. Lewis grasped the same truth: “Nothing that you have not given away will ever be really yours. Nothing in you that has not died will ever be raised from the dead. Look for yourself, and you will find in the long run only hatred, loneliness, despair, rage, ruin, and decay. But look for Christ and you will find Him, and with Him everything else thrown in.”

Friendship with Christ means friendship with the One who has the power to give us the life eternal we crave.

And so, there is a second inscription at the monastery. It is hidden away in a secret garden at the very center, accessed only by those monks who have long practiced giving up the world and vowed themselves to a holy life.

The words are cut more deeply than those on the exterior; they are larger and more permanent; in them is the real meaning of the first inscription, it’s apex and fulfilment:

“Nothing is Lost.”

(Sight Unseen is an occasional column that explores God and the world. Brandon A. Evans is the online editor and graphic designer of The Criterion and a member of St. Susanna Parish in Plainfield.) †

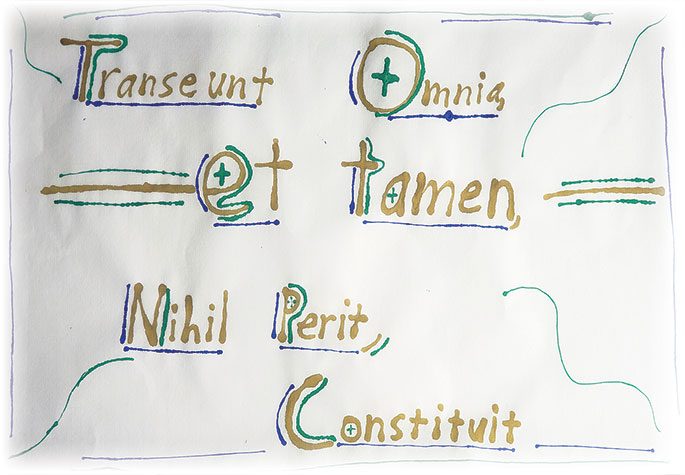

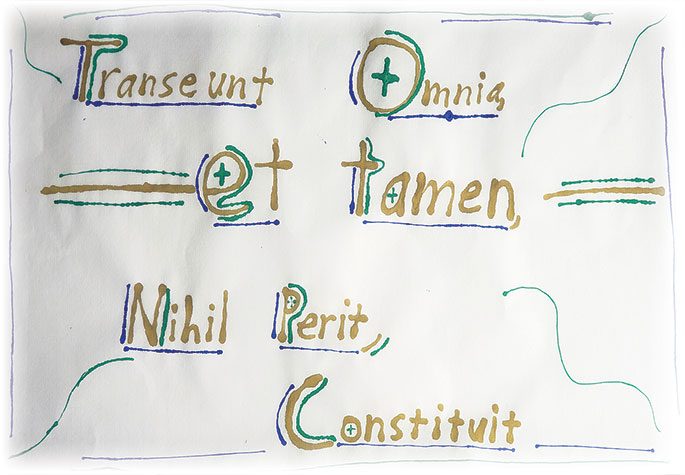

The Latin phrase above, written on rice paper with fountain ink, reads “Transeunt Omnia, et tamen, Nihil Perit, Constituit,” which can be roughly translated to: “All Things Pass, and yet, Nothing is Lost.”

In a distant land, there is a fictional monastery and over its church is a stone mantle. Inscribed there are three words its monks read every time they gather to prayer:

In a distant land, there is a fictional monastery and over its church is a stone mantle. Inscribed there are three words its monks read every time they gather to prayer: