Reflection / Brandon A. Evans

Missing from the Shroud of Turin

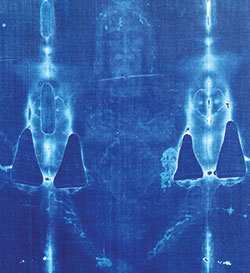

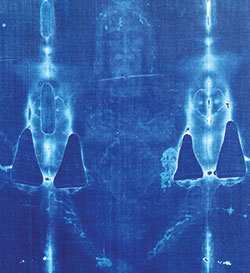

This color negative of the Shroud of Turin is taken from the original photograph shot by Barrie Schwortz in 1978 and includes places where the relic was damaged in a fire. Schwortz was the official documenting photographer for the Shroud of Turin Research Project in 1978—the first extensive scientific examination of one of the holiest relics of Christendom, which is housed in the Turin Cathedral in Italy. (©1978 Barrie M. Schwortz Collection, STERA, Inc.)

There is something missing from the Shroud of Turin.

Something so obvious, and so strange, that it would be altogether noticed—and rather quickly—if not for the context of the image, which is that of a dead man.

Still, it’s something that very nearly every painting or drawing or depiction of Jesus Christ contains, even those of him dying on the cross.

I would dare say it would have been his most striking feature, and that its absence could very well be a providence to all who look upon the relic with weakened, human hearts.

It is odd, in a sense, because the Shroud of Turin holds nothing back. The figure it depicts is naked, front and back. It is covered in wounds of flayed open skin and puncture marks. Blood has posthumously flowed onto the fabric.

The man’s nose looks crooked from a beating. His beard and mustache are unkempt and, like his hair, matted with dried blood. His countenance is one of a person who, having given everything, has ceded to death.

There is, of course, debate around the Shroud of Turin, just like many other Catholic relics, and there always will be. The initial carbon dating 30 years ago, along with the written historical record of its existence, suggest a medieval origin. But other evidence, equally scientific and logical, suggest a lineage far older.

If one assumes that the Shroud of Turin was the actual cloth used to wrap the body of Jesus Christ after he was taken from the cross, then the image—placed only on the tips of the linen fabric by a method not yet able to be reproduced—is quite miraculous.

For it is more than an image: it’s a photograph from the distant past. It is the face of Christ lay dormant in a negative image 1,800 years before photography was invented and another 70 years before anyone thought to apply the principles of film to the shroud. It’s a face that speaks to us in the language of modernity: a photorealistic image unlike anything we have prior to 1826, least of all from the time of the Roman Empire, and even more least of all from the most important person in the history of human life on the planet.

Supposing that Jesus meant for us to have this image, this one image, of his human likeness, why? Why something so gruesome? So sad?

Perhaps because the image on the shroud is imminently approachable. No one could fear to draw close to such a man. He is beaten and laid low. His face, though wounded, has a certain serenity. The Jesus of the shroud waits peacefully and gives us the chance to not only come close to him but to see what cost love paid for our souls, and to be grateful to him.

This is Christ the King as he begs us to see him in the Gospels. Not a conqueror or a tyrant, neither rich nor proud, but a man of meekness and courage who stood face to face with death and despair and loneliness for us, and defeated those fiercest of demons using only his weakness.

This is a God who, to paraphrase C.S. Lewis, stoops to save, and is not too proud to help us “even though we have shown that we prefer everything else to him.”

One possible religious explanation for how the Shroud got its unique image is that is was burned there by a supernatural light at the Resurrection, making the shroud, like Christ himself, a place where the worldly and the divine intersected.

It would also mean that the image we see was taken in the very last moment that death had reign over the world. The man of defeat we see became—at that very instant—the Risen Christ, the cause of our joy and salvation, the head and heart of the Church, the life of the world and the King of heaven and Earth.

Half a second later something happened that Jesus seems to have specifically willed not to be shown on the Shroud of Turin.

He opened his eyes.

The eyes that could see through flesh and bone to the hearts of men both wicked and saintly; the eyes that could discern intention, and from which no truth could hide even among the cleverest of lies.

The sight of those eyes is what gave the most wretched of sinners and the most crippled of bodies a hope beyond hope. But they also drove to fury and hatred the arrogant and self-assured.

We will see those eyes in person one day and they will do the same to us, one way or the other.

They will be a balm to the afflicted and a horror to the proud. They can be nothing other. There is no middle ground there; if the eyes are the window to the soul, then the eyes of Jesus are a window to eternity and a devastatingly honest mirror for each person.

But for now, that terrible gaze is closed, and we are spared its finality. What remains of our lives is nothing less than the time to draw nearer to the living Jesus, who calls out to us—even from a photograph—to come closer and closer until our souls, unafraid and pure, can stand in the fire of those eyes.

(Brandon A. Evans is the online editor and graphic designer of The Criterion and a member of St. Susanna Parish in Plainfield.) †