A light in Africa:

Brother and sister keep the faith in fighting health crisis

By John Shaugnessy

By John Shaugnessy

The frustrations and the doubts sometimes gnaw at Dr. Ellen Einterz and Dr. Bob Einterz—trying to tempt the sister and brother from giving up their goals of changing minds, changing lives and even changing the world.

Listen to us, the doubts try to tell the sibling doctors who grew up in St. Matthew Parish in Indianapolis: There’s too much heartbreak in Africa, too much horror in AIDS pandemic that devastates millions of families, and

Bob Einterz too little help in turning the tide against death and disease on that continent.

So, the doubts continue, “Why don’t you just walk away, Dr. Ellen, from your hospital in Cameroon where the people keep coming and coming with endless cases of malaria, malnutrition, cholera and AIDS? You’ve put in more than 20 years of your life in

Africa. What more can anyone expect you to do?”

Then the doubts turn to Bob,

founder of what is regarded as one of the best AIDS treatment programs in Africa—the IU-Kenya Partnership between the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis and the Moi University School of Medicine in Eldoret, Kenya.

“Dr. Bob,” the doubts say, “the AIDS crisis rages on in Africa. Take a break from nearly 20 years of trying to make a difference on that continent. It’s your time to try something else.”

The doctors’ answer to the frustrations and the doubts can best be captured in a moment that Ellen experienced in Cameroon, a moment she wrote about in her ongoing

newsletter to her supporters: “One Friday night, in the middle of a howling dust storm, see you are trying to start a transfusion on a gasping 7-month-old

boy who appears to have not a

single vein in his entire body. You are bent over him,

ready to try a second or a third stick when suddenly the

lights go out. In the darkness, the boy, his eyes rolled back

into his head, is struggling for every breath. You could

send someone into town to fetch the man who is in charge

of the generator, but that would take 45 minutes.

“Or you could leave the ward and go out to the generator

house and start the engine yourself, but that would take

half an hour, and you don’t know whether this child has

even 15 minutes of life left in him. So you ask someone to

light a kerosene lamp, and by the orange glow you carry

on, trying to find the elusive vein in time to keep that life

under your hands from going out like the electricity.

“You find it at last, and it is not too late. The blood starts

flowing, and not much later, the bony chest starts heaving a

little less desperately and the grey cheeks begin to lose their

ghostly pallor and finally the mother’s solemn face relaxes

and streams with tears of silent joy. And it occurs to you that

that must be one of the most beautiful things it is possible to

witness anywhere on earth.”

The influence of family and faith

The themes of light-in-darkness, hope-against-doubt, and

life-amid-death resonate through the lives of Ellen and Bob.

“We’re both helping to provide health care for some of the most desperate people of the world in sub-Saharan

Africa,” Bob says.

As he talks in his office at Wishard Memorial Hospital

in Indianapolis, Bob sits near Ellen. Although they share

a focus on health care in Africa, this is one of those rare

moments when the well-traveled, different roads of the

brother and sister have led them to each other. Ellen only

returns from Africa for three months every two years.

Minutes ago, the conversation revolved around how

Ellen literally carried Bob on her back as a child and how

she taught him to read. Now, the conversation turns to the roots of their relationship as part of a family of 15, and to the roots of their desire to heal others. They both talk about the influence of their Catholic faith and their parents, Frank and Cora.

“Growing up in a family of 13 kids, you learn very quickly you are not the center of the universe,” Ellen says. “There are all kinds of people, and you have to get along. Our parents were raised in the Church, and their faith was very important to them. They let us know we are one small part of a greater world.”

They both remember their father telling them and their siblings, “We are Christ, you are Christ, our neighbor is Christ.”

“Our parents had this notion of teaching us to live our faith and live out our faith rather than wearing it on our sleeves,” Bob notes. “We are given gifts, and we have expectations to use those gifts. Those are lessons from our faith and our parents.”

A different path

That faith and guidance have steered them both in the direction of Africa, a continent where more than 17 million people have died from AIDS and another 25 million are

infected with the virus, according to DATA, an organization

dedicated to raising awareness about the AIDS crisis.

Bob and Ellen also know that the disease has infected nearly 2 million African children, and 12 million African children have lost one or both parents to AIDS.

One of Bob’s greatest fears is that future generations will look back on the AIDS crisis in Africa and say that people didn’t do enough to stop it, that they chose to stand by and let it happen. Neither he nor his sister has made the choice to stand by.

Ellen started her path at 19 when she served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger in 1974—a time of a major famine in that African country.

“I saw carcasses everywhere,” she recalls. “It just looked like there was so much that needed to be done. It was there that I decided to become a doctor. I wanted to return to a place like that where I felt I would be desperately needed.”

After medical school, she returned to Africa, spending six years in a Nigerian mission clinic before heading to Kolofata in Cameroon in 1990. When she first saw the hospital in Kolofata, it took her breath away—for all the wrong reasons.

She remembers the hospital as being dilapidated and strewn with cobwebs, a place where thick red dust coated everything. As bad as it looked to her, it was viewed even

worse by the local people. They saw it as a place to die, and they avoided it at all costs. In the beginning, they avoided Ellen, too.

Yet when an epidemic of meningitis swept through a village, she was there to help. When only one person died, the trust in her began to rise.

“I clung to a trusted mantra from my marathon running days—just keep putting one foot in front of the other—and every once in a while, I could look back and see the distance that we had traveled,” she wrote in one of her newsletters to friends and family in America.

The view looks considerably different 16 years later. With her leadership, a new hospital was built, a hospital that includes a children’s pavilion and a maternity and surgical ward. She has also trained nurses, directed the building of health centers in isolated villages and opened a women’s edu-cation center where women and girls learn to read, write and develop skills that can lead to an income.

“It’s 100 percent hands-on working with the people,” says Ellen, now 51. “I run six health centers and the referral hospi-tal for this district. I’m responsible for the health care of 109,000 people in a very poor, very isolated area of Cameroon.”

A significant part of the funds for her efforts and the build-ing projects have come from the parish where she grew up— St. Matthew.

“Ellen is the nearest thing to Mother Teresa I’ve ever met,” says Father Donald Schmidlin, a former pastor at St. Matthew. “Her whole attitude of being in Africa is it’s such a privilege because they welcome her willingness to help. I just admire her whole attitude and courage and skill. It’s just so remarkable, and it seems to run through the family.”

Reaching out in need

In his office, Bob looks at Ellen and says that she has always set the standard for him. She is the second oldest of the 13 siblings. At 50, Bob is the third oldest. He followed her example and served in the Peace Corps in Haiti. His focus is also in Africa.

Yet Bob long ago moved out of Ellen’s consider-able shadow. Since the late 1980s, he has left his own distinctive mark through the IU-Kenya Partnership—a partnership he helped to found, a partnership that has led to the treatment of 30,000 HIV-positive patients at 18 clinic sites in Kenya.

Bob has lived and worked in Kenya, but now his role as the partnership’s director keeps him in Indianapolis, overseeing the financial aspects of the program, planning its strategic growth, and coordinating relations with the United States government,

Kenya’s government and others who help fund the $12

million-a-year program.

“I feel a sense of responsibility to do my part—and I feel that strongly,” says Bob, now a member of St. Monica Parish in Indianapolis. “The difference now is that I do this almost completely vicariously. If I had my druthers, I just want to be a doctor. But I also realize what I do is important.”

Still, amid the strategy sessions, the financial concerns and the bureaucratic red tape, the human element is always in his view. A framed photograph of a group of Kenyan children orphaned by AIDS holds a prominent place on one wall in his office. In his briefcase, he also carries a photo of an ill Kenyan child to remind him of the true purpose of his work.

“It’s the people that drive us,” he says.

The partnership provides food assistance and job training for HIV-positive patients and their families. It sends medical students from the IU School of Medicine to train and help with the AIDS crisis in Kenya. It has also created AMPATH, an Academic Model for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV/AIDS.

“To even the casual observer, it has been a miracle,” notes Dr. Joe Mamlin, a co-founder and the field director of the IU-Kenya Partnership. “If Bob had decided to work from Kenya, there would be no program. He had to gain the support of donors, write some of IU’s largest grants and assemble a con-sortium of collaborating U.S. medical schools.”

Still, Bob dreams of doing more, motivated by the success the partnership has had in treating AIDS patients.

“Ultimately, what we hope to see is a comprehensive, primary care program that’s accessible to the populations we serve,” he says.

A remedy for doubt

Even as the doubts and the frustrations occasionally come, the commitment continues for the two doctors.

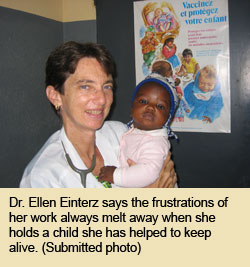

“Every day, I’m faced with real suffering in children who I know would die if I wasn’t there, babies who wouldn’t live if I wasn’t there,” Ellen says. “My remedy for moments [of doubt and frustration] is to go back to the hospital and find a patient. That remedies the situation.”

All the years, all the sacrifices, all the heartbreak, all the hope come down to one fundamental approach to life.

“For me, the bottom line is reading the Gospel and trying to understand how Christ lived and trying to follow it,” Ellen says.

As her brother nods in agreement, she adds, “At every fork in the road, you choose to think about what’s right.”

(Anyone wanting to contribute to Dr. Ellen Einterz’s efforts should follow these steps: Write a check to St Matthew Church. In the memo line on the check, write “For the Dr. Ellen Einterz Project.” Send a note and the check to St. Matthew Church, 4100 E. 56th St., Indianapolis, IN 46220.) †

By John Shaugnessy

By John Shaugnessy