Reflection / Brandon A. Evans

The surprise of impossible beauty

The darkness in the light.

The darkness in the light.

That phrase had been rattling around my mind for the past few years, in large part as a phrase that summed up what I imagined a total solar eclipse to be and what I hoped to see when traveling to Chester, Ill., on Aug. 21 with family and friends.

All the pictures rightly show a pitch black moon over the face of the sun: a dark star hovering in the sky as though it’s punched a hole in it. People who follow eclipses talk about seeking to live again in the great shadow which sweeps over whole countrysides.

Indeed, before the eclipse began the only questions everyone wanted to know were: Where is the moon now? What side will it come in from? And once the partial eclipse starts, everything becomes about the moon and how much of the sun it’s taking away. For anyone outside the narrow band of totality the partially obscured sun is the high point.

For those in just the right spot, the darkness takes center stage late in the eclipse as the vista around you seems both more dim and more crisp at the same time. People start mentioning it. A peek to the horizon shows what looks like a storm coming in.

It’s only after the last bits of sunlight, dodging through the craters and hills of the moon, start to twinkle out and the shadow of nightfall rushes upon you that everything suddenly flips.

The entire storyline, in one second, changes. It’s not about the darkness at all. Everything that came before—all the planning and driving and worrying and waiting—it all steps to the side. Something appears that wasn’t there before. That wasn’t there ever. Mouths gape open. People cheer, then fall quiet.

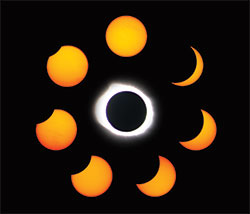

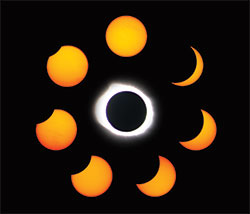

A collage of images taken in Chester, Ill., of the Aug. 21 total solar eclipse shows the unobscured sun at the top, continuing counterclockwise with images of the partial eclipse. The totally eclipsed sun radiates in the center. (Graphic and photos by Brandon A. Evans)

Up high, in the open air, is something that shouldn’t exist: a void in a twilight blue sky, from which flows not shadow but light: delicate filaments of silken white reaching out gently into space.

All my preparation and pre-conceived notions were wholly inadequate. There is no picture that does justice to the sight of the sun’s outer atmosphere streaming out of utter blackness. No light I have ever seen matches the purity of the corona, invisible in every other circumstance but this. There was a fearful sense of being on another world.

The revelation hit me just how much had to go right for this to happen: from the weather to the size of the sun to the distance of the moon. The coincidence is staggering.

In a moment, two minutes and 39 seconds jumped past me. But in that moment was a hidden eternity in the form of a crisp and permanent memory.

When the first, blinding beam of sunlight shot out from the far edge of the moon, daylight instantly returned, as did the whole world with it. Time began moving again. I understood why people wait so long and work so hard for just a few minutes under a shadow: it’s because they come for the light.

The Bible is pregnant with the idea that there are things just beyond the reach of this world that are unspeakably beautiful—that despite the chaos of mortal existence there is a master plan.

A total solar eclipse is probably the natural example par excellence of the triumph of Jesus Christ on the cross: the moment, the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, when just as all the evils of the world rose up against him on every side, the sacrifice of Christ secretly became the source of all salvation (#1851). From the darkness sprang the light, as it did in the beginning of time during creation, and as it will in the end when all things are made new.

Each of our lives leans toward the hope of such a twist ending whereby the wrongs and woes of our days, against all odds, are made whole again. Like the fading light before an eclipse, we pray that our darkest times may turn out to be the necessary preparation to allow something spectacularly more marvelous to be seen.

To witness a total eclipse is to suddenly realize just how true the promises of the Gospel are—that there really are splendors that eye has not seen and ear has not heard waiting just beyond our humble lives.

The wonder of an eclipse is the surprise that above you all along, hidden in plain sight, there has been an impossible beauty: the light from the darkness.

(Brandon A. Evans is the online editor of The Criterion and a member of St. Susanna Parish in Plainfield.) †

The darkness in the light.

The darkness in the light.