Medical students taught to offer human touch to terminal patients

By John Shaughnessy

The tears of the first-year medical student touched Dr. Gregory Gramelspacher as he listened to her describe the impact that a patient’s death had on her.

The tears of the first-year medical student touched Dr. Gregory Gramelspacher as he listened to her describe the impact that a patient’s death had on her.

Joanna Fields had just met the patient months ago, but her regular home visits with the dying, elderly man changed their relationship and her approach to becoming a doctor. She grew to care for the terminally ill patient as a person.

“He knew he was going to die, and he still had a good attitude,” recalled Fields, 28, a student at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. “He passed away over Christmas break. When I heard about it, I prayed and I cried.”

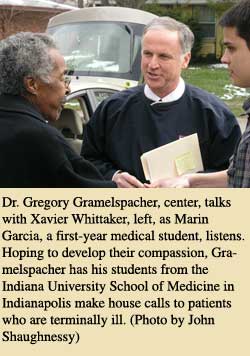

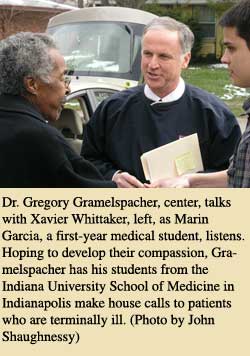

Developing the care and compassion of Fields and other medical students is the goal of Gramelspacher, a member of St. Luke Parish in Indianapolis who matches the students he trains with terminally ill patients.

Similar to his students, Gramelspacher also makes house calls for people who are poor and dying. He even gives them his business card, encouraging them to use his pager number when they need his help.

For Gramelspacher, it’s all part of his mission to offer a human touch to the dying while training a new generation of doctors who will see the importance of letting people die with dignity.

“What you do in the care of your dying patients is as important as anything you will do in your medical career,” Gramelspacher tells the students.

Those words get the students’ attention. The 1975 graduate of the University of Notre Dame also wants to get the attention of the medical community, to make it look beyond the approach of extending life at all costs.

“One key to change is to have a kind of physician who is so dedicated to their patient that their oath is, ‘I’m not going to allow you to have an ugly, painful death,’” said Gramelspacher, who also directs the palliative care program at Wishard Health Services in Indianapolis. The program focuses on making death more peaceful and relatively pain-free for its dying patients, many of whom are poor.

The 52-year-old doctor often asks the medical students if they’ve ever been with people when they’re dying. At least half of the students usually say they haven’t.

The experience has been educational and moving for Anne Gabonay, 24, a first-year medical student who is also a member of St. Christopher Parish in Indianapolis.

“It’s about living better,” Gabonay said. “Part of living better, I think, would be dying better. Being in the home, you not only get to listen and learn from the patient, you also get to listen and learn from the family members.”

The house calls transform students in other ways, Gramelspacher said.

“One thing they need to know is that there’s hospice or how someone can die at home surrounded by family and friends,” he said. “I’m all for good death. I will often say it’s in God’s hands, not the doctor’s hands.”

That faith also frees him to reach out toward patients with a human touch that often gets lost amid the machines and the medical technology.

“I pair medical students with a terminally ill patient during the first week of medical school,” he said. “It exposes them to death and dying. It exposes them to home visits. Patients are shocked. I give them my card with my name and my pager on it. I want to get called. The patients don’t abuse it and their families don’t abuse it. It reassures patients.”

Janet Parrish and Xavier Whittaker are both terminally ill patients in Indianapolis who say they have been helped by visits from the medical students, Gramelspacher and other doctors.

“It’s wonderful,” said Parrish about her visits from Stephen Rush, a 26-year-old, first-year medical student, from Indianapolis. “He knows what he’s talking about, he knows what he’s doing, and he listens and understands.”

Doctors need to make that emotional connection with dying patients, Gramelspacher said, so they can treat patients with compassion, respect and dignity.

“We have to help them walk with patients and families through this tough time,” Gramelspacher said. “There’s such a huge need.” †